“Please people with likerous voice?” Sound and Belief in Late Medieval England

“Please people with likerous voice?” Sound and Belief in Late Medieval England

Thomas Kaal

t.kaal@ghil.ac.uk

My project investigates intersections between sound and belief in late medieval England. Integrating approaches from the history of the senses, the history of experience, and liturgical as well as musicological scholarship, it develops a framework for understanding the significance of auditory engagement in medieval religiosity.

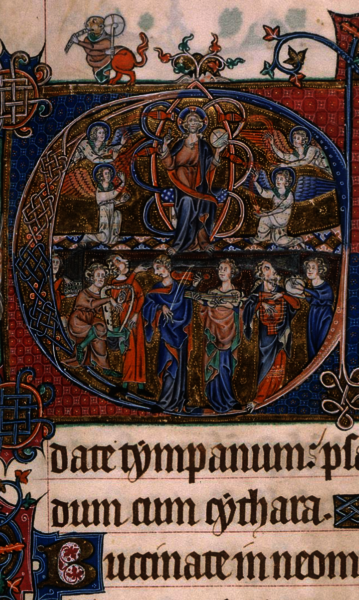

As scholarship moves beyond mentalistic or dematerialized conceptions of belief, questions of emotion, embodiment, and performance have gained increasing attention. In the medieval period, this applies particularly to the sonic realm. The sound of medieval Christianity permeated communities across the social spectrum and all stages of life. Possible engagements were not confined to the hours of service or the church’s interior. Sound was carried into everyday life through hymns, processions, and the ringing of church bells echoing across the landscape. Heard in different contexts, it generated varying opportunities for response. Devotional attention was only one possible reaction. Sounds could also be ignored, perceived as a distraction, met with skepticism, or condemned as lustful or demonic. My project explores how sound materialized in spaces of unequal reception and representation, where it acquired religious significance through culturally conditioned modes of listening and response. Examining these dynamics thus not only offers insights into personal religiosity but also connects the topic to broader questions about cultural contexts, social structures, and gender roles. What people heard, when, and how often—as well as their participation—was often determined by rank, age, gender, and education. Conversely, auditory habitus also contributed to the construction of social roles and shaped ideas about femininity and masculinity. While they were clearly relevant on an individual level and reflected idiosyncratic sensibilities, religious sounds thus functioned as a potent means of community formation—reinforcing unity and belonging while at the same time enabling exclusion and othering. As socially, culturally, and morally mediated phenomena, auditory practices both reflected and reinforced hierarchies and power structures, making them inherently political.

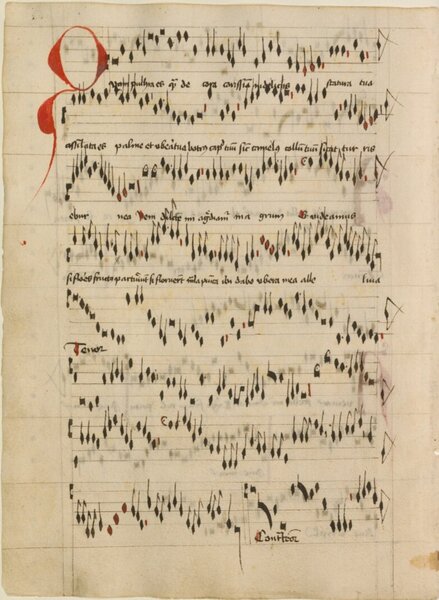

In late medieval England, the spread of liturgical polyphony, coupled with reformist pressures in the wake of Lollardism, provoked disputes over what constituted proper and improper uses of sound and music. From the early fourteenth century until the English Reformation, these debates surfaced in sermons, theological treatises, polemical tracts, and inquisitorial proceedings. Taking the controversy as a point of departure, my project examines the interplay of sound and belief on three interconnected analytical levels: first, by exploring exemplary cases of soundscapes in late medieval English towns and monastic communities, relying on documentary evidence and visitation records; second, by examining the discursive construction of hearing in sermons, devotional literature, and polemics; and finally, by engaging critically with historiographical traditions that, in reinforcing the centrality of vision in post-Enlightenment epistemology, project radically different sensory regimes onto premodern societies.