A Secret Artifice: Language Invention in the Age of Global English

A Secret Artifice: Language Invention in the Age of Global English

Dr Pascale Siegrist

+44 020 7309 2016 p.siegrist@ghil.ac.uk

The history of language invention is commonly told as a story of failure. In this version, a pragmatic and imperially connoted ‘global English’ established itself as the world language in the interwar period – at the expense of the idealistic international auxiliary languages of the likes of Volapük, Esperanto, and Ido. Yet, as I aim to show in this project, this transition is better thought of as a shift towards new types of artificial languages. In this study, I read the language invention initiatives of English speakers as a response to the globalisation of their mother tongue; an experience that had inevitably transformed their understanding of the relation between language and culture.

The study thus stresses the historical and contextual drivers of language invention. In so doing, it takes issue with classifications of artificial languages along etymological and functional lines. I argue that the motives for language planning evolved considerably over the period marked by the two world wars, and that this was reflected in changes not just in language planning as a phenomenon, but at times even within a given artificial language and its community of speakers. The boundaries between practical and fictional uses were in flux, intended and actual applications did not always correspond.

At this stage of the project, I am pursuing three interrelated hypotheses as a lead to read the renewed productivity in language invention in the English-speaking world against the backdrop of the emergence of English as the world’s language.

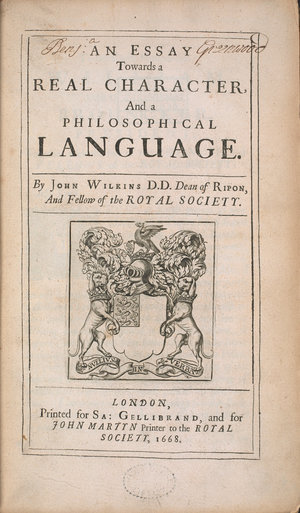

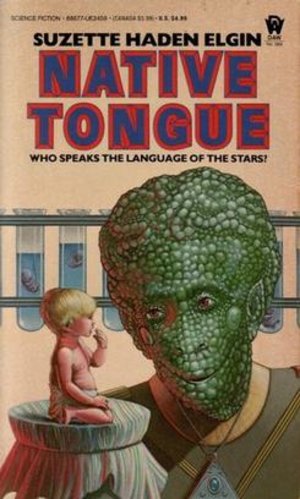

First, I want to suggest that the interwar period witnessed a slow transition from invented languages in the service of universal understanding and harmony – ‘for one humanity, one language!’ according to Volapük’s mission statement – towards what J.R.R. Tolkien in a 1931 lecture referred to as ‘a secret vice’: private languages invented for the aesthetic pleasure of their creator and a small circle at best. Second, focusing on (discrete) language invention as a tool of linguistic exploration rather than as a practical means of communication, I want to raise the question of the extent to which the twentieth-century experimentation with language construction represented a return to the distinctively British tradition of the philosophical languages of the seventeenth century. For seventeenth-century language inventors, the ‘philosophical’ nature of their creation meant that it was universal and potentially accessible to all human beings, while for their twentieth-century counterparts language invention aimed at demonstrating, and potentially transcending, linguistic relativism. Their inventors began to see artificial languages as a hermeneutic tool for putting theories of linguistic universalism / relativism to the test; either in positing a strictly logical language supposedly devoid of all cultural signifiers (such as James Cooke Brown’s Loglan), or, to the contrary, in exploring the possibility of a consciously and radically positioned language (such as Suzette Haden Elgin’s women-centred language Láadan). In step with the general shift of the centre of gravity of the Anglosphere across the Atlantic after World War II, the United States gradually took over from Britain as the leading motor of artificial language making, with outliers also in the decolonising world: tracing this shifting topography is the third aim of the project.

With chapters consisting of case studies discussing individual language projects and their authors – linguists, philosophers, and writers of (science) fiction, with many combining all three roles – the study testifies to the intimate connection between language-making and world-building. For historians, the case of constructed languages offers a rare glimpse of language not as an ex post and descriptive marker of historical change but as a normative and prescriptive attempt at past world-making.